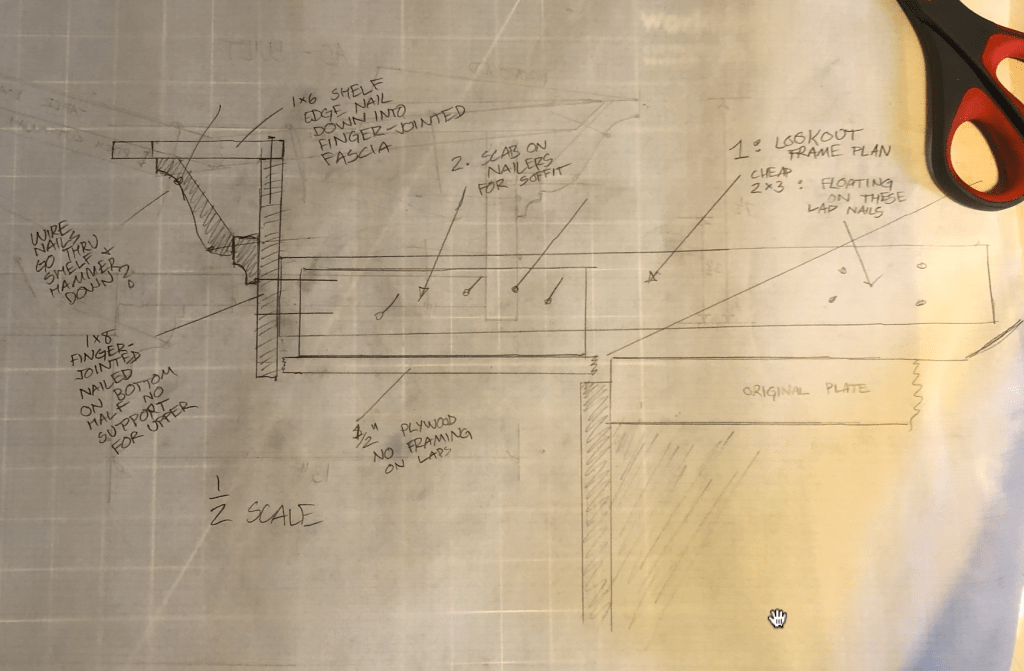

rob unversaw of Rockdale Construction: framing plan fail

here is what Robbert built.

truly shameful and unprecedented. The lookouts were floating, lap-nailed. The sill under, rotted in many places. The shelf and cornice is held on by finger jointed interior trim, wire nailed to end grain. All of the historic wood which needed to be stripped and repaired right, was glued together with another layer of caulk and spray on paint.

Styling an addition to a Victorian wood house

I don’t care for stick frame wood houses from any era: but here we are stuck with them all over the landscape. These structures have far less integrity than brick or stone. Most of them can be expected to last 16-20 generations. About 1/3 of the lifespan of a comparable brick structure. Thats still enough lifespan to justify preservation though, for the good examples of the building method.

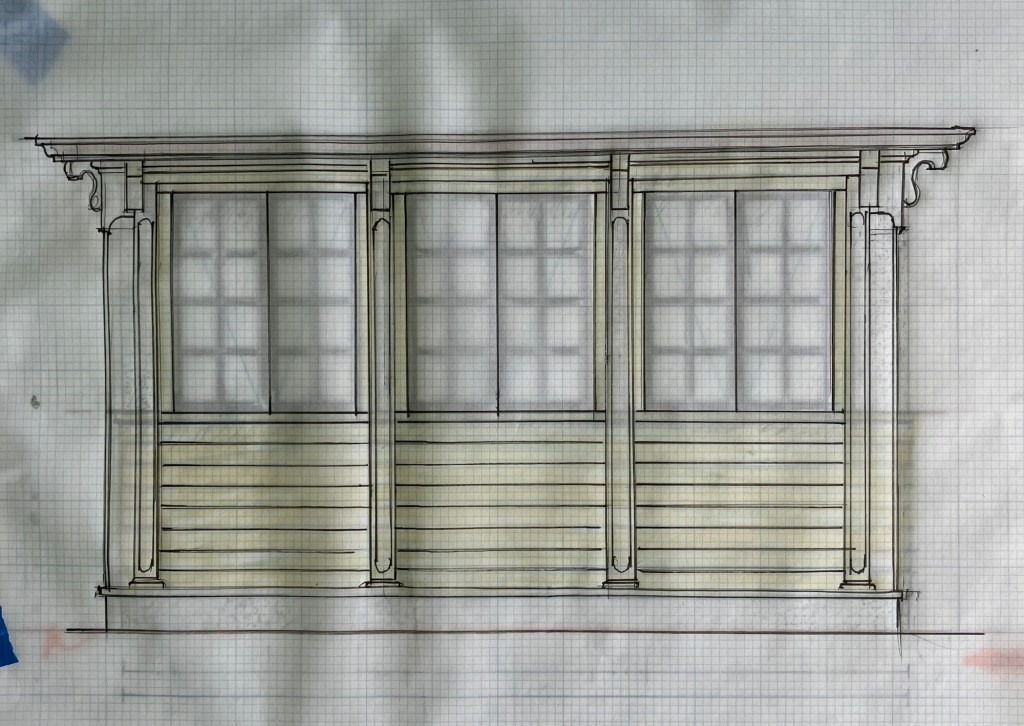

This challenge involved taking a 20th century porch addition and styling it to make sense with the rest of the house.

My first idea was to punctuate the addition and date it in the arts and crafts era. The theory being: an addition should read as an addition and not attempt to “fake” consistency with the rest of the building:

This design features a shiplap lower apron, continuous sill, and stucco wall finish. Simple 1×6 trim for the windows.

The next design is more in keeping with the style of the house. It features a paneled layout with the trim reduced and pilasters defining the layout. The corbel brackets from the main cornice are repeated here and carved half-round reliefs are used to give the trim pilasters some texture.

The “fancy” one would take nearly double the labor and demands high grade materials for the sill, moldings, and pilasters so it’s a real show off, for a small addition to an already grand structure.

Arts and farts.

Correcting a half-cooked McMansion with proper structural methods and regional pattern language.

The first draft featured a misguided mansard, 2 wythe wall, foam, veneer walls, concrete slabs, false walls and drywall, and a horrible user experience within the floor and stair plan.

The building as designed by Pless is no better than a typical office/commercial structure. Consuming a lot of barcode materials and proprietary engineered “structure”.

This revision maintains the “impressive” symmetrical entry but cleans up all the appliqué. The garage structure is no longer an appendage with the same roofline. Instead it’s punctuated as a utility building separate from the main. Using a mews pattern with parapet gables.

The bloated lawyer foyer is gone and in its place is a classical 3/4 stair with a landing at the lantern window over the front entry.

Gone is the fake cornice. In its place is a brick corbel, and simple soffit and fascia with a standard hung gutter inset to stand as the cyma recta.

Midweek update

There hasn’t been too much photogenic work since I completed the tiny bathroom. In the last weeks we moved a bunch of dirt, did grounds work, cleaned and performed quarter-making duties.

The “apartment” is almost livable with a few quirks remaining. I have to perform extra labor to hang dry clothes and I’m chopping veg on a short table instead of a waist high counter-top. Theres no freezer so i travel on the bike to pick up ice. I can’t store any meals for deep freeze. There’s no stove or oven just a toaster oven and microwave. Meal planning and level of service available to guests is very low class because of these constraints. I certainly can’t invite good people over for dinner in this mess. It’s a lot like being on a ship when you live on location.

The dust and remediation of lead pollution topsoil is nearly complete.

Next task: dig out completely under the porch and tuck point the wet foundation with hot mixed lime mortar. It will be sound for another 7 generations after that work.

Weekend update

Things are cooking here at the North Star of Winfield. We finished the half bathroom walls, trim, and flooring..

I started Friday morning laying on my back in the hole tacking up pipe straps and eating cobwebs and dust for breakfast…

Justin kept me motivated and ran cuts while I was fussing with the heavy tongue and groove flooring. Todd learned how to bullnose a rail with a palm sander. Everyone got red deck stain all over their hands…

My next job after the bath is finishing the As-built historical documentation. It is nearly complete but I have a few more built-ins and doors to document before they are dismantled for paint stripping….

In the wee hours during the hail storm I inked in this perspective cutaway of our main public room, the east door delivers you to the business center and service counter.. and a small dinging area with a armchair 2-top and 3 top cafe table in the bay window.

The west door leads to the bar and large dining room, with several 2-tops, bay window 3-top; and a large 4-top booth anchored on the west window.

Weekend update

This weekend we really got to work together like a team. Justin helped me keep this jobsite clean, ran the vacuum and handed me water cigs and tools while I was crouched in the hole.

He learned how to remove a toilet without spilling water everywhere, dismantled multiple layers of flooring and patches. We made one trip to the big box store for fixtures and finishes, and one trip to the lumber yard for framing and flooring lumber.

I will complete the framing and install the fixtures and flooring this week. The whole family comes down next week and we will get to paint the trim and decorate/pick a ceiling color.

By god we will have one finished room in this house. Come Saturday we will be shittin’ pretty in the restored half-bath.

Weekend review

TO: Justin / FROM: Kurtis

I woke up early Sunday. Greeted by a train whistle and just the crickets. In the still morning air you can hear dew dripping off the Lady and quenching the yard. Everywhere I look things are proper. put away stored with care, stacked, counted. This indeed looks like a happy house and a place where some very capable men are working

I want to personally thank you, Todd, and Justin once more for your performance this weekend. The grounds feel inviting even though it’s a jobsite. I’m very impressed with your work ethic.

Thank you for respecting my leadership and allowing me to bark orders at you like a mean navy dyke. It was truly an honor to mush you dickweeds around. Looking forward to every session. Even the shitty ones.

The ladies in the wall are extremely happy with how their house is looking.

-Sincerely, Kurtis Hord, Caretaker and Producer

Old Depot Public House.

Protected: Packing inventory

The socialist case for Trad Architecture

Ask a conservative why Britain’s cities and towns often look so ugly, and you’ll likely be told that it’s intentional: the result of post-war utopianism and the establishment’s inexplicable embrace of modernist architecture. For the traditionalist magus, Roger Scruton, such a development was “the greatest crime against beauty the world has yet seen”. In this account, it is the fanatical architect, zealous planner, and toadyish politician who are to blame for the handsome streets of yesteryear giving way to atomised ruin. The malaise may be aesthetic, but its roots are moral.

What is not asked, however, is why? Why did Britain, and much of the West, suddenly insist on remaking the built environment at such speed? The idea this resulted from a sudden bout of cultural self-loathing is supported by no evidence. The same is true for the notion that despite founding Nato and trying to maintain its empire, post-war Britain was somehow stuffed with surreptitious Marxists, from the commanding heights of Westminster to the planning offices of your local town hall.

Like most simple, comforting stories, this is wrong — a convenient narrative for inaction and self-satisfied moaning. What is needed instead is a Marxist, materialist account of why the built environment changed as it did. History, after all, is not forged purely by ideas.

What does a materialist analysis tell us? Firstly, that conservative concepts of beauty are incongruent with a devotion to the free market, something which Marx identified 150 years ago. Capitalism, driven by a relentless quest for profit, requires constant spatial transformation. This means we have the buildings we do because, for the most part, somebody somewhere is making a buck. This is difficult to grasp for many on the Right because they have elevated profit into a kind of ethical value (although this wasn’t always the case). But it should be relatively obvious, and far less outlandish than the idea that your nearest Wilko or TK Maxx looks the way it does because of the malevolent influence of Oscar Niemeyer. As Marx wrote in The Communist Manifesto: “All that is solid melts into air; all that is holy is profaned.” This is why a commitment to the free market, and to social and aesthetic conservatism, are irreconcilable.

This is most conspicuous today with Purpose Built Student Accommodation (PBSAs), those modular ziggurats afflicting skylines across Britain, from Altus House in Leeds to Beckley Point in Plymouth (each is the tallest building in their respective city). In Cardiff, more than 7,000 student “flats” were built in just three years.

These buildings are springing up like medieval Bolognese towers for two reasons: firstly, because the building standards are lower for student developments than either residential housing or housing in multiple occupation; and secondly, because building them is lucrative. Forget Marxist council officers and architects with fantasies of becoming the next Frank Gehry. These buildings are being assembled in the quest for profit.

In Portsmouth, the city centre has now essentially become a student campus, the city’s sense of civic pride sacrificed to corporate student accommodation and fast-food outlets zipping deliveries to them via smartphone. It’s a grim vision of what our smaller city centres are becoming, with spaces for interaction in short supply. In Bournemouth, where I grew up, a seaside town synonymous with Victorian and Art Deco architecture looks increasingly like the set of the Teletubbies. Any sense of place is out of the question, the objective instead being to turn the town into a giant airport terminal.

Another important reason for those tragic “before and after” pictures so beloved of Trad Architecture Twitter is the popular adoption of the car in the mid-20th century. As with the failure to grasp the contradiction between free markets and conservation, this too is lost for many on the Right (although, in his defence, Scruton once referred to cars as “dangerous weapons”). This shouldn’t be overly surprising given the automobile was synonymous with personal freedom, an avatar of the sovereign individual conquering the elements. What is forgotten with this blanket projection of personal autonomy, detached from society, is that the dense patchwork of urban settlement that preceded it was lost. You may be able to go anywhere in a car, but you do so by cutting yourself off from others. In the words of Kafka: “you are free, and that is why you are lost.”

The reconfiguration of streets around the car is the principal reason cities such as Birmingham, Glasgow and Bristol lost much of their lustre. This was not limited to Britain, of course. Take the story of Robert Moses, the subject of Robert Caro’s magnificent biography The Power Broker. Over several decades as a public official in New York, Moses gleefully destroyed downtown areas often marked by cultural and racial diversity, as well as high density construction. The reason? To build expressways.

The Cross Bronx Expressway offers the best example of this, ripping as it did through the heart of what would become the northern and southern parts of the Bronx. Things could have been worse, however. And it was only because of civic resistance, led by the likes of Jane Jacobs, that the construction of the proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway was stopped. Had she failed, it would have destroyed much of what is SoHo, Little Italy and Chinatown.

While it’s true that an infatuation with the car was central to post-war planning, today it is the Left leading the movement for low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs). By contrast, it is Conservative councils, such as inSouthampton or Wandsworth, that are reversing them. This is not to say all LTNs have been executed well, but it is clear that reducing our dependence on cars has become a part of the culture wars, with conservatives often on the wrong side. It’s one thing posting nostalgic pictures of yesteryear; it’s another to do the hard political yards to reverse mistaken choices since.

This bizarre confusion is most obvious in Poundbury, the experimental community built on land belonging to Prince Charles. Even here, in a place whose premise is a return to tradition, the civic centre of Queen Mother Square is a car park. Even if you embrace the orthodoxies behind the project (I personally find it more akin to a Las Vegas theme park), it’s hard to see how rows of hatchbacks and people carriers continue the legacy of Victorian or Georgian architecture. It’s the same in the village of Wickham, home to the second largest medieval square in England. The Visit Hampshire websiterefers to the village’s “15th century cottages” and “beautifully preserved Georgian houses”. Yet such wonders are also now obscured by the fact that the village square is now a rather large car park.

When it comes to the built environment, it’s easy to lapse into mistaken binaries. On the Right, conservatives wish to retain a distinctive architecture. They claim to want to “conserve” buildings whose qualities transcend present, fleeting sensibilities. They believe in objective standards of beauty — be they from antiquity, or the work of Palladio or Wren. The Left, meanwhile, is apparently driven by a fixation with the future, a permanent experimentation with forms and an impulse to discard the old.

And yet much of this narrative doesn’t align with reality. Councils of all stripes are gleefully granting permission for hideous student blocks, while a Conservative government oversees our rivers being pumped with effluent. Meanwhile, it is progressives who make the arguments for more humane environments where we use our cars less and enjoy a slower pace of life. They don’t always get everything right, but there should be no doubt that active travel, living streets and low traffic neighbourhoods are the simplest ways to begin making our towns and cities beautiful again.

All of which is why the socialist case for respecting architectural heritage should not be at odds with a small ‘c’ conservative approach. This should be the opposite of the promethean road-building projects of the last century, while also avoiding a swivel-eyed hatred of more recent architectural heritage, whether that be the Barbican in London or Berlin’s Palace of the Republic. Take the brutalist Trinity car park in Gateshead. Conservative critics may think such buildings shouldn’t exist by default, and so it was demolished in 2010. Yet it has been replaced by a Tesco — hardly a win for Scrutonian beauty and the public good.

Finally, socialists and conservatives alike must understand that the built environment, as with every human endeavour, is an inheritance from one generation to the next. We should be humble rather than dismiss the ideas of those before us, regardless of which century they come from, while also asking what kinds of structures will fill our descendants with wonder. As Stephen Nachmanovitch wrote: “If we operate with a belief in long sweeps of time, we build cathedrals. If we operate from fiscal quarter to fiscal quarter, we build ugly shopping malls.” The enemy of beauty isn’t “modernism”; it’s a society built on maximising profit and shareholder value.

You must be logged in to post a comment.