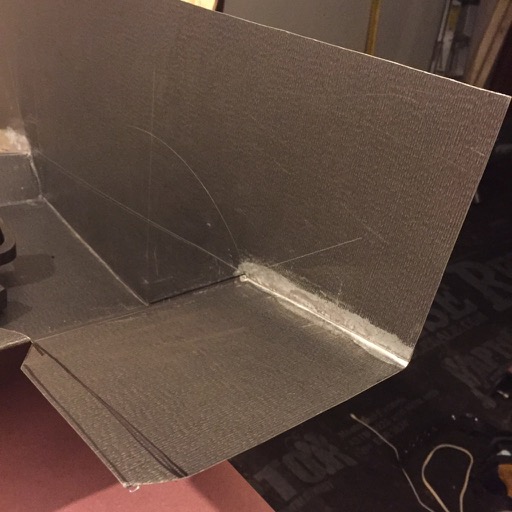

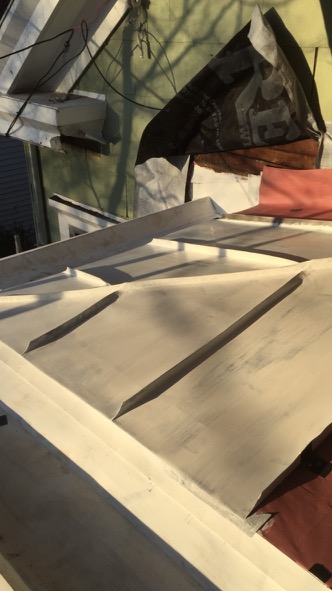

The snow aprons were completed and slate started going on this weekend in Titusville.

The Internet's Own Historic, Traditional, and Permanent Building HQ

The snow aprons were completed and slate started going on this weekend in Titusville.

Comrade: Aidas Danisevicius shares photos of his boyhood home? The post includes video of a roof tour, and up-close photos of the joinery. They claim the house is from 1600. I have my doubts that the roof is original, but it’s very early: at least and century and a half, maybe two from my experience surveying similar old roofs in america on aged structures.

Jana Hodúrová shared a post to the group: КИЯНКА.

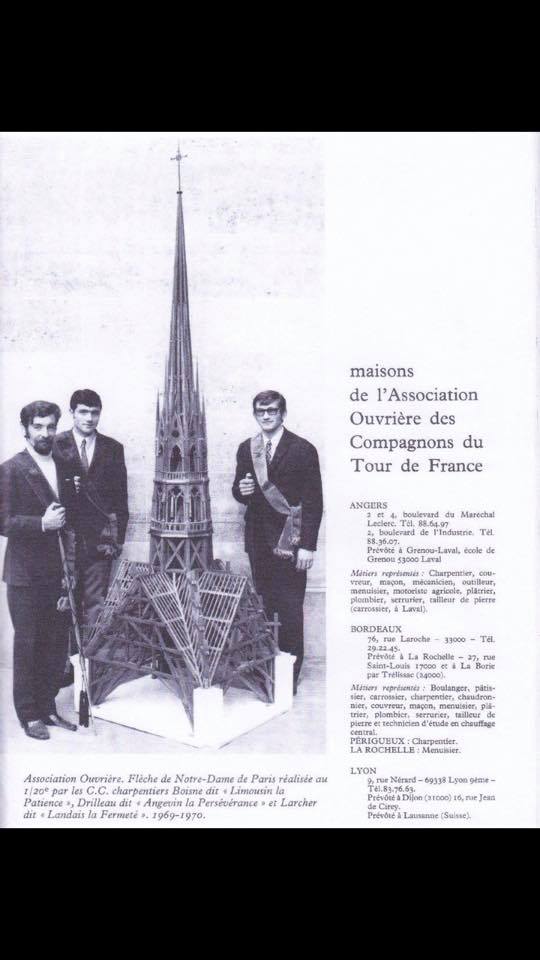

In the lore of the traditional French carpenters guild, the compagnon charpentiers, Notre Dame is a sacred structure. For a timber-frame carpenter with a particular interest in historical French carpentry, this is a difficult situation. I have been deep in correspondence with my colleagues in the hours since news of the fire. Here are my initial reactions:

I am glad to have spent some time around the cathedral while visiting Paris last October at the end of a tour of French carpentry museums, and I have good reason to be hopeful about the future of this building. The fire is a catastrophe, but the skills and passion to rebuild this structure are present in the compagnon craftspeople of France like in no other western country. The traditional knowledge that originally built this monument is still alive. The Compagnons du Devoir actively transmit this knowledge to young people through intensive, long-term apprenticeships, setting a high standard against which to measure any vocational training.

There is hardly a more well-documented building anywhere in the world, and traditional craft knowledge can fill the gaps of any architectural survey.

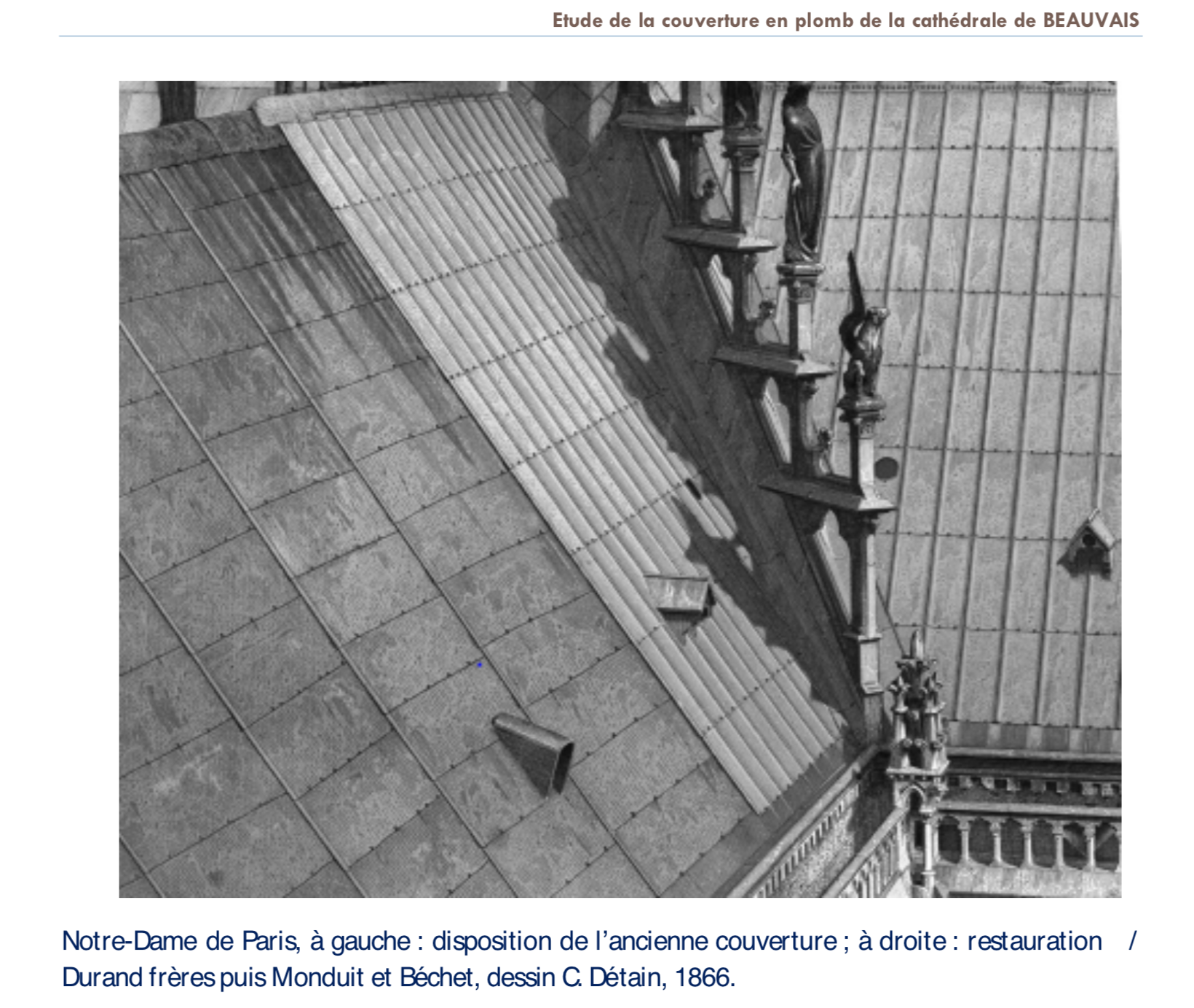

It’s easy to lose sight of history, including architectural history, as an evolving process. While some parts of Notre Dame are over 800 years old, and built upon prior ruins, its famed spire was designed by Viollet le Duc and completed in 1859, over 30 years after Victor Hugo wrote The Hunchback. At least one of the massive rose windows was replaced in the 1960’s. Maintenance is a necessary and continuous process tying the past to the present, ensuring a future for history, as the massive scaffold enveloping much of the cathedral recently attests.

Shinto shrines in Japan are entirely rebuilt on a regular schedule, the Ise Grand Shrine every twenty years, 62 times. This is a radically different approach to maintenance than we are accustomed to here in the US or Europe, its critical function to train subsequent generations of craftspeople. The longevity of these shrines rises from the spirit and continuity of their creators and supporters, not from a faith in persistent materiality alone.

A similar spirit brought members of the Timber Framers Guild together with international volunteers to create a replica of the Gwoździec synagogue in 2011. This structure now represents the lost wooden synagogues of Eastern Europe in the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, on the site of the Warsaw Ghetto.

French culture, with the compagnons at the ready, is uniquely prepared to deal with the fire at Notre Dame, and to benefit from the audacity of its grand scale. Smaller reconstruction projects are always underway throughout the country, even to the extent of Guédelon, an experimental archaeology project to create a new 13th-century chateau.

One of my greatest worries at the moment is that any efforts to rebuild the lost structure might be hampered by requirements to use modern materials, in a well-meaning but mistaken attempt to improve upon the original. I don’t think the original can be improved upon, and its soul would be lost in the attempt. Additionally, no modern materials have proven as durable as the original stone, wood, and lead, each of which can be maintained and repaired indefinitely. Buildings must inspire care to long persist, something no technology can replace. Far better for any reconstruction to be carried out in the full spirit of the original work, by committed craftspeople setting their efforts in search of the ineffable.

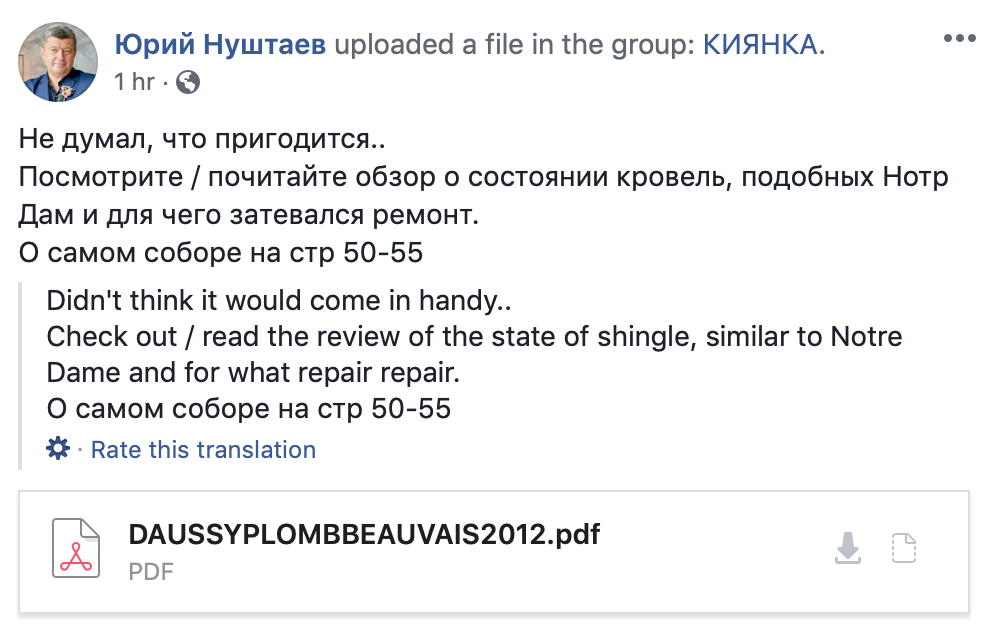

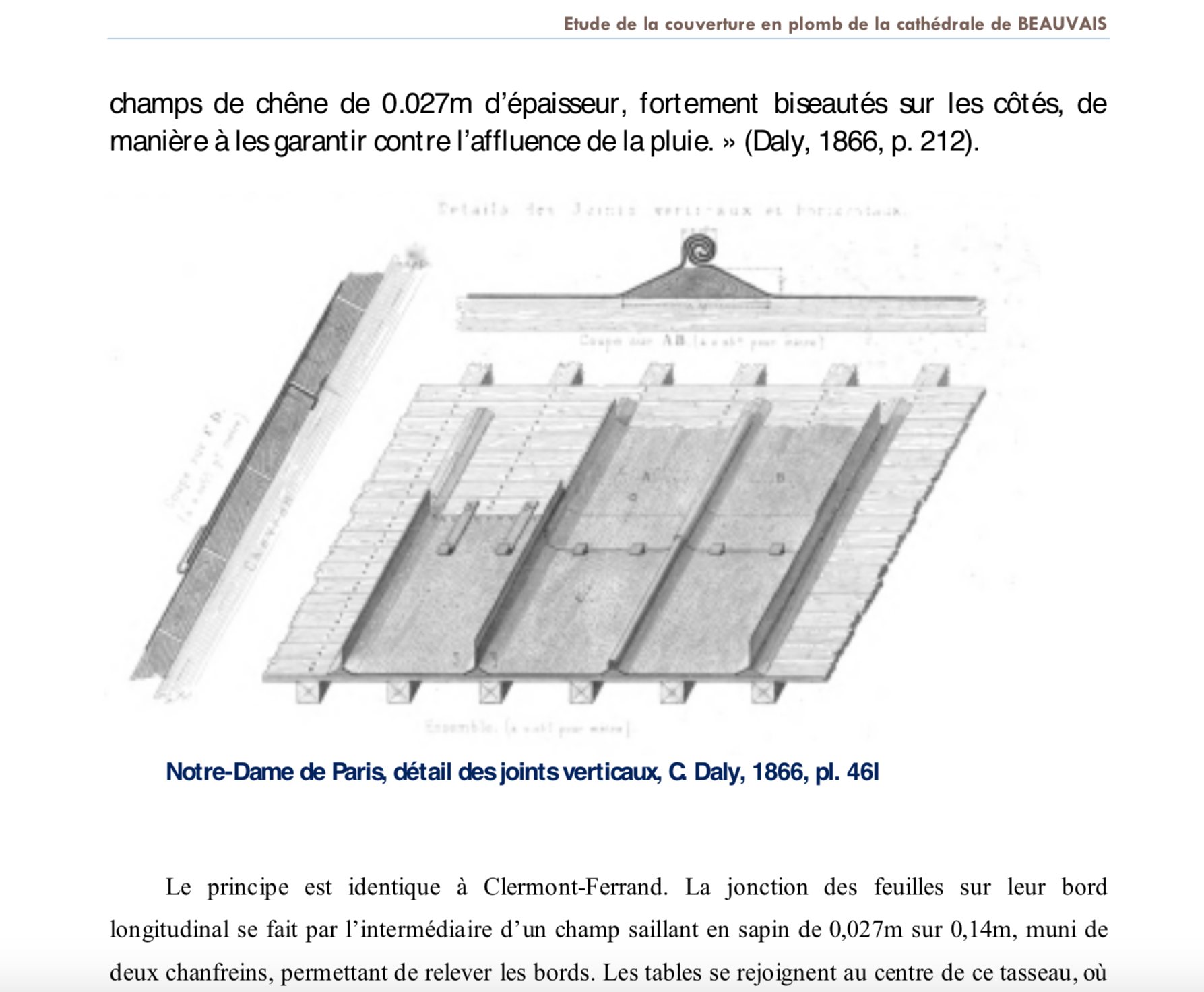

Comrade: Alexandre Lepand who works as a roofer in France posted some photos from his personal collection of the notre dame roof up close.. Looks like it was cap-and-pan lead.

What we lost… and why it matters.

comrade Igor Konovalov

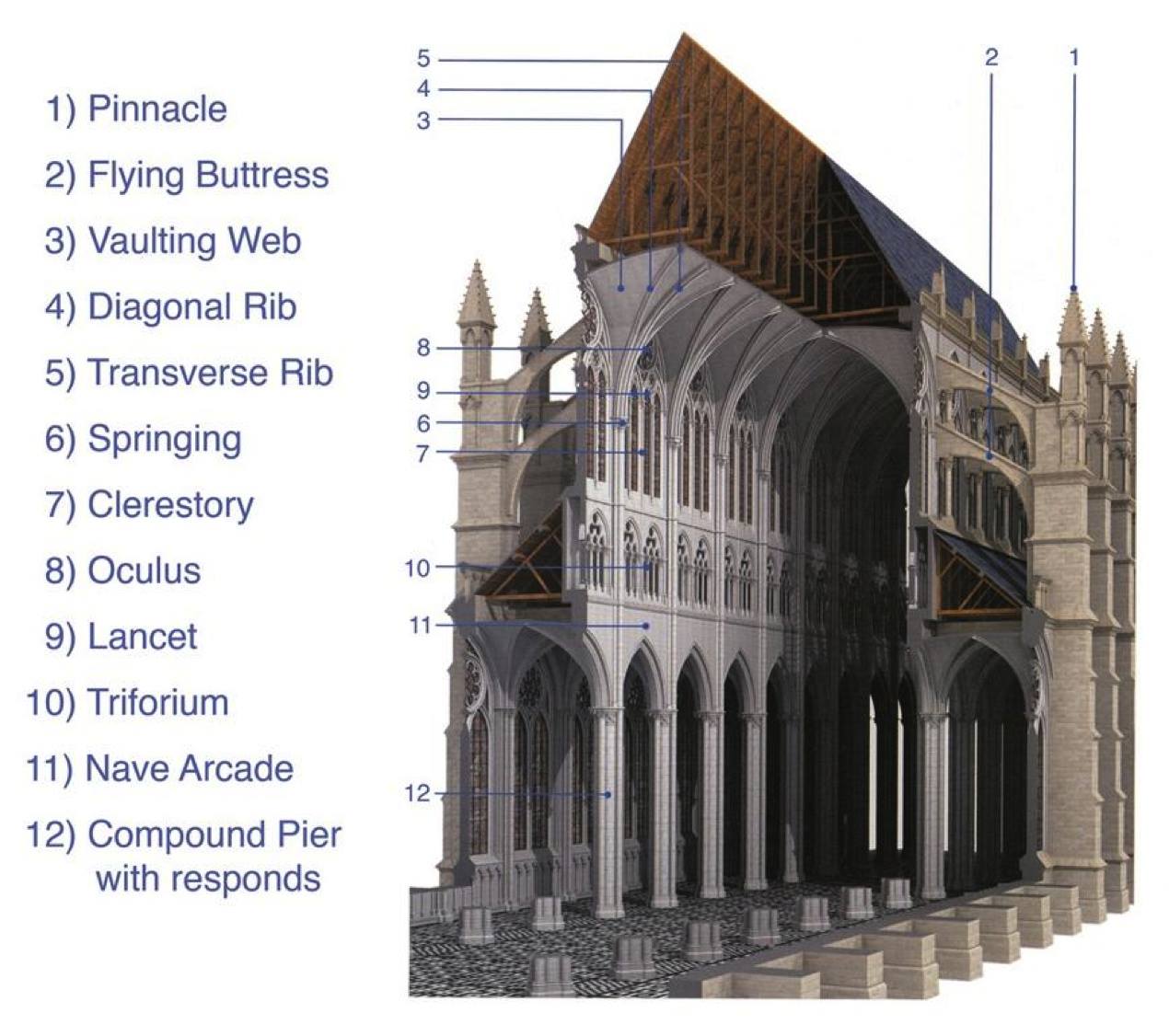

This image shows the construction of a typical French Gothic cathedral. The overcroft, the area above the vaulting (the ceiling you see when you look up) is an elaborate wood structure, often refereed to as a forest, supporting the roof. Some of those wood beams were over 100 meters long and dated to the 13th century. Heat reached 800 degrees C, destroying that forest and the roof. There is also extensive water damage.

Most of the stone is still standing, but every piece of stone and all the mortar joints will need to be carefully assessed for heat damage. The stone vaulting did cave in at three locations; the crossing, which is the center under where the spire collapsed, and in the transepts. The three great rose windows appear to be intact; glass melts at about 1500 degrees C; but every piece of glass and all the lead caming holding it together will need to be examined. Art works are being moved to the Louvre for safe keeping.

So far over €300 million has been pledged for restoration, but it will take much more than that to bring this world treasure back. Our hearts go out to France.

I watch these demolition notices for historic structures in the west end of louisville go through my inbox every week. It’s hard to look at sometimes. This one is no exception.

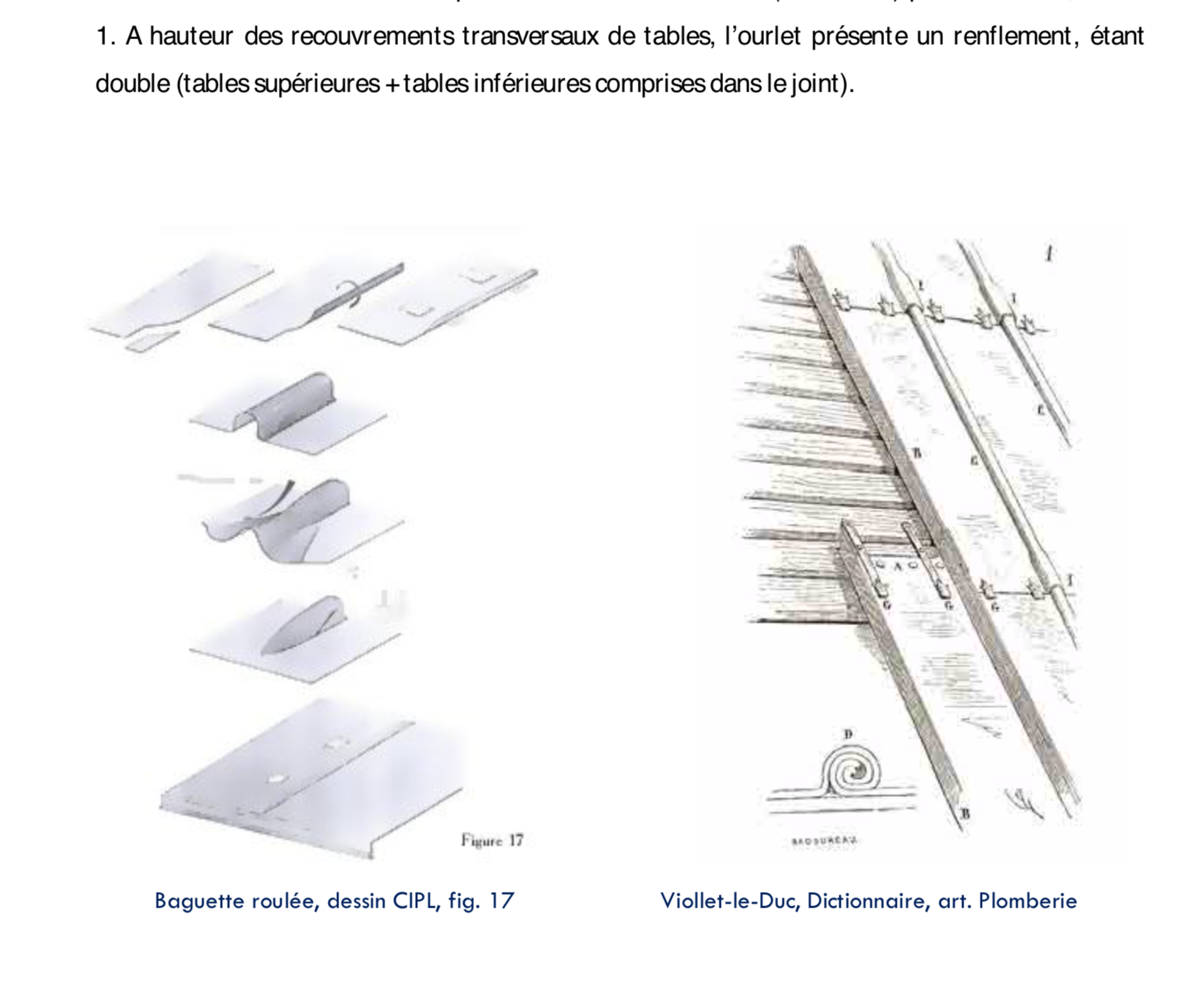

It is a real shame to see this over and over and over again. There are a lot of American historic roofers who have only ever known flat lock. I will continue to shame them.

Flat lock, was a mistake in the past and it is still a mistake today. Roof tinners in early America developed flat lock, out of necessity and ignorance. They had complex shapes to cover, and they had no guild training so they weren’t aware of free seaming without solder. It was a “good enough” approach.

Why is this bad?

You must be logged in to post a comment.