While I was searching the Building Technology Heritage Library for a duty-free copy of Neubecker, I came across a new resource (to me).

The Anaconda Copper Mining Company, part of the Amalgamated Copper Company from 1899 to 1915,[1] was an American mining company. It was one of the largest trusts of the early 20th century and one of the largest mining companies in the world for much of the 20th century.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anaconda_Copper

The specs here are for 10oz copper, what they call “economy” roofing. I assume from the title, the marketing, and the specs it was offered less to promote permanent roofing, and more to sell copper. We would never use 10oz copper for a roof.

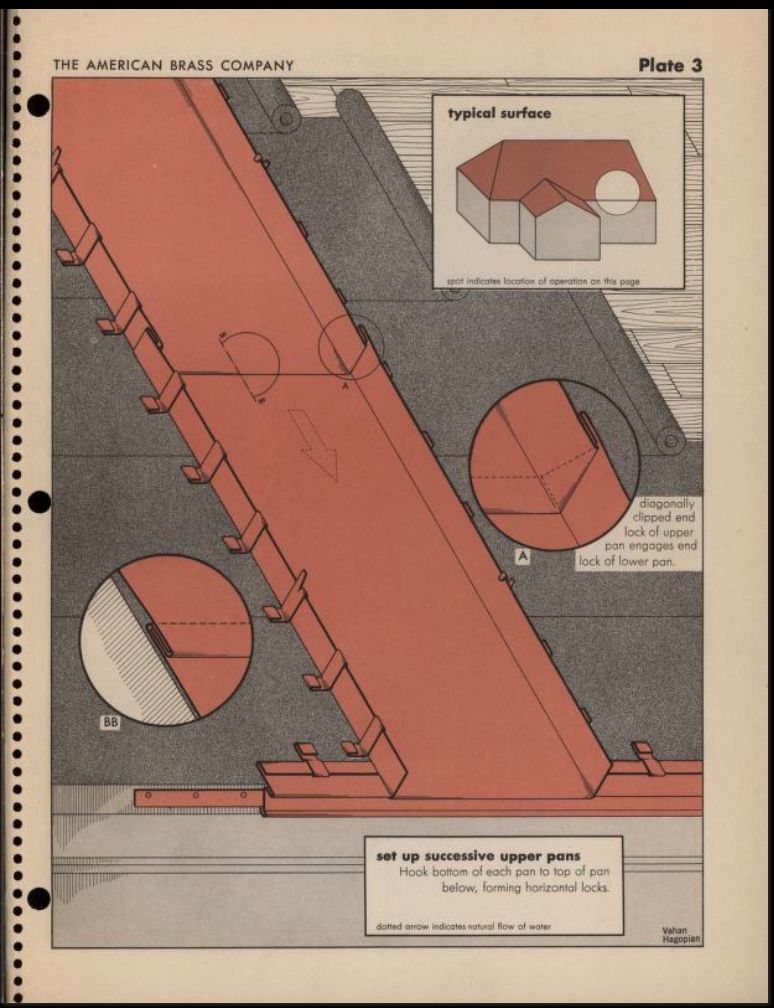

Right away, we are treated to incomplete information, and oversimplification… showing transverse seams. It gets worse on the next page…

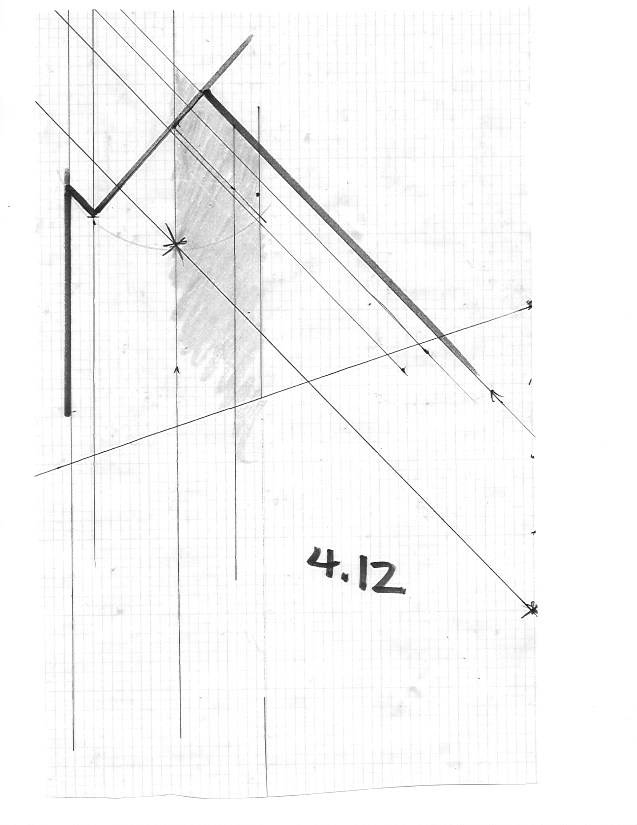

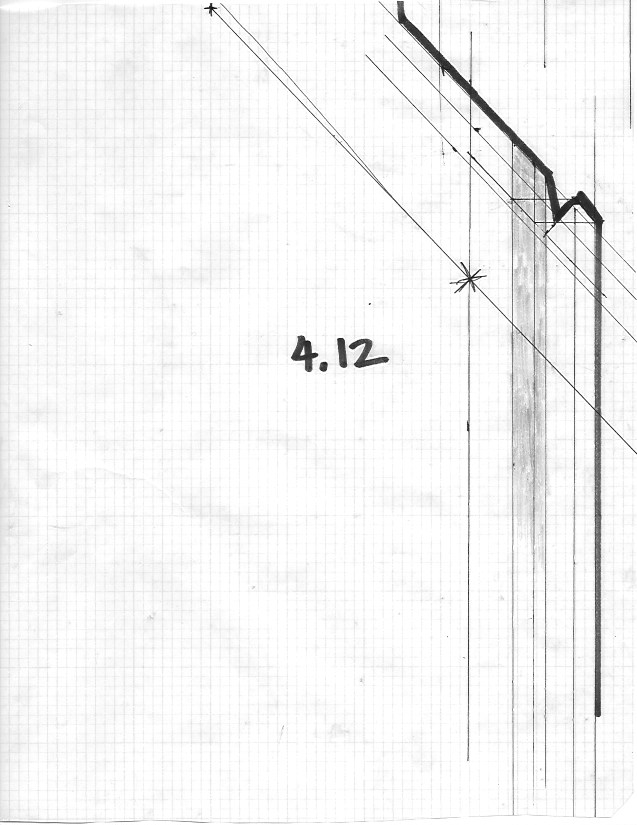

Fixed clips can only be used on short rafters. (less than 28′). When you join the pans together with the field seam it creates columnar strength that essentially makes it a single pan. This is the hard lesson learned by those in europe who were tasked with replacing their own failing designs. The roof works against the fixed clips and eventually works them out, causing a wholesale failure over about 200 years. While this would be a decent life-cycle for most, we are striving for better and we now have the knowledge to do better. A general rule of thumb: if you are creating a copper roof that needs more than 2 10′ pans, incorporate expansion clips. Further: the roof needs a fixed point in the middle, for low pitches, and higher up the roof depending on pitch. This is to account for “critical loading” where the weight of the roof itself starts to bear on the clips and fasteners as the pitch increases. For a steep roof: the fixed clips are placed almost near the top, with expansion clips below.

So what’s wrong with this? Several things: the rules dictating the use of transverse seams are completely reliant on the pitch, and overflow/backflow conditions. Further they don’t demonstrate what the rules are for creating the notch. This is covered with more clarity in a modern resource:

Even with these rules of thumb, it’s important to realize other factors can determine the use of a wide-notch transverse seam at low pitch.. It can only be used in un-obstructed field where there is no risk of overflow.

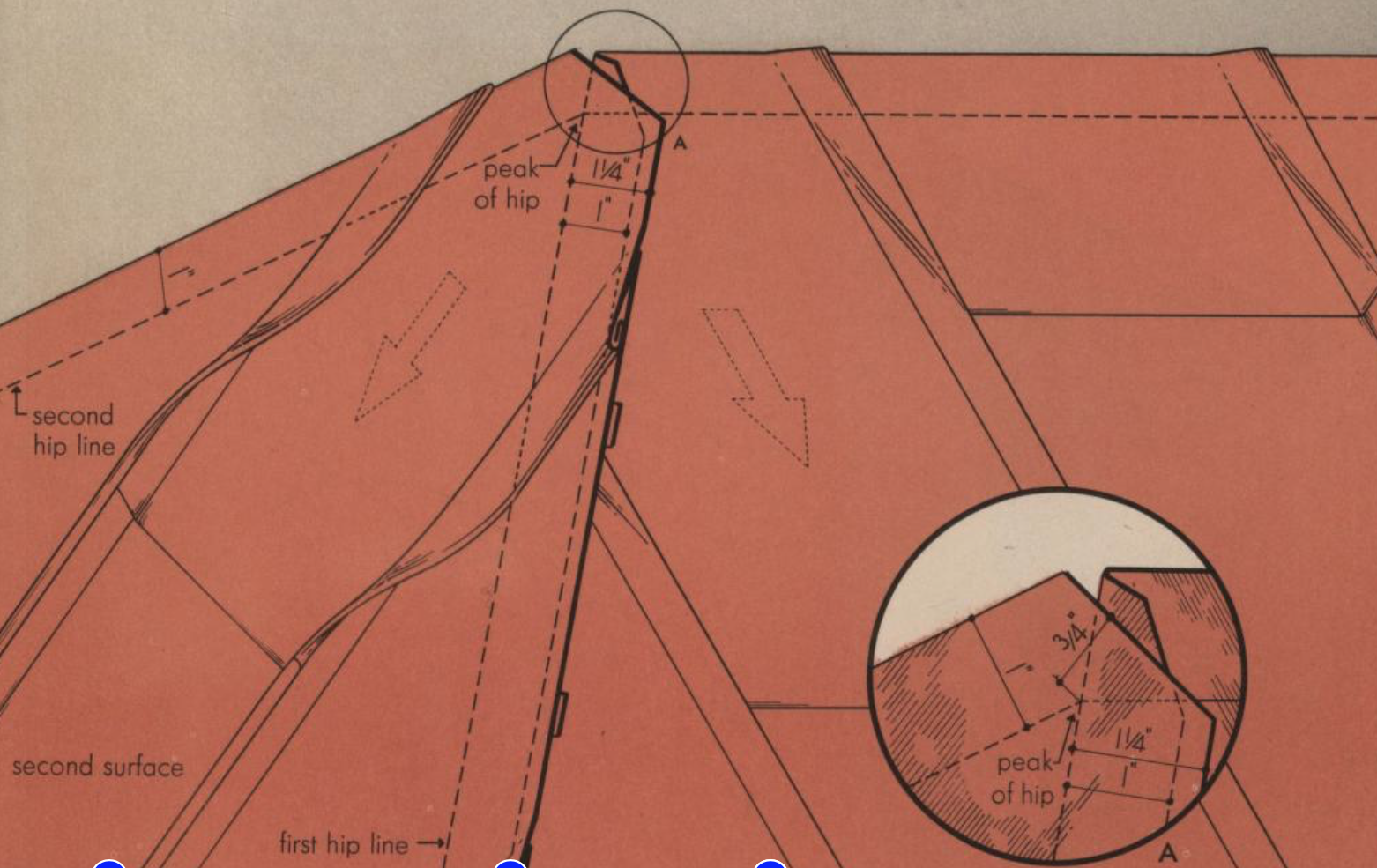

A few pages later, we see some very simple hip “instructions” showing dead-cut full seams with no notching. It was possible to fold a light-gauge steel roof with no notching to the pattern, but it’s not recommended. Anyone who has attempted to fold 6-8 layers in copper knows this.

While I was excited to see a reference showing the actual folding of hips and ridges, this ultimately does not help the installer create a permanent assembly as it could be with the proper planning, and care to joinery. It is better than Neubecker’s treatment of standing seam, but only gets us about halfway there.

This goes to demonstrate the main issue with knowledge of metal roofing in America. We assume that historically: they knew what they were doing but our references compared to similar work and knowledge from the old world shows this is not the case.

You must be logged in to post a comment.